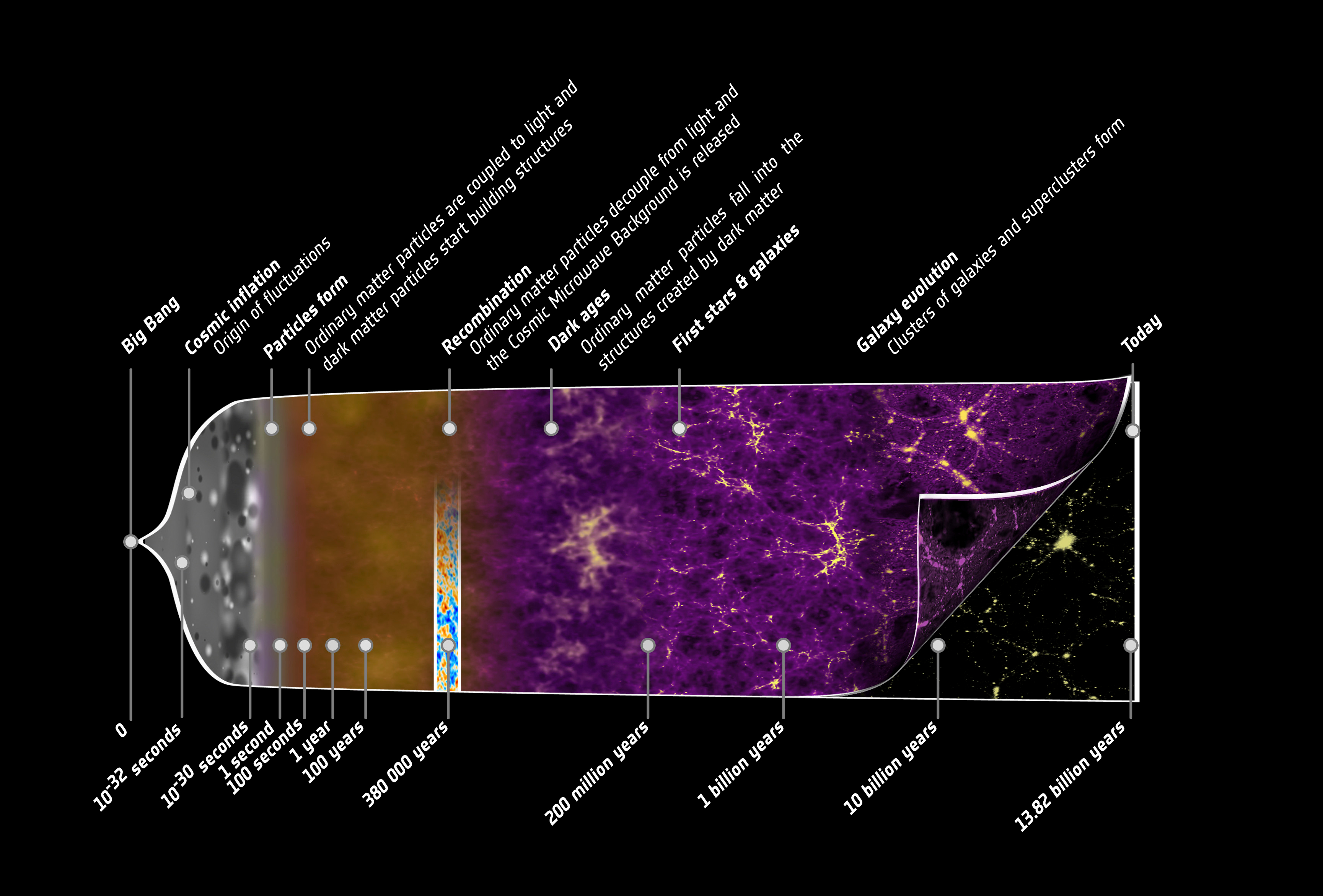

Big Bang

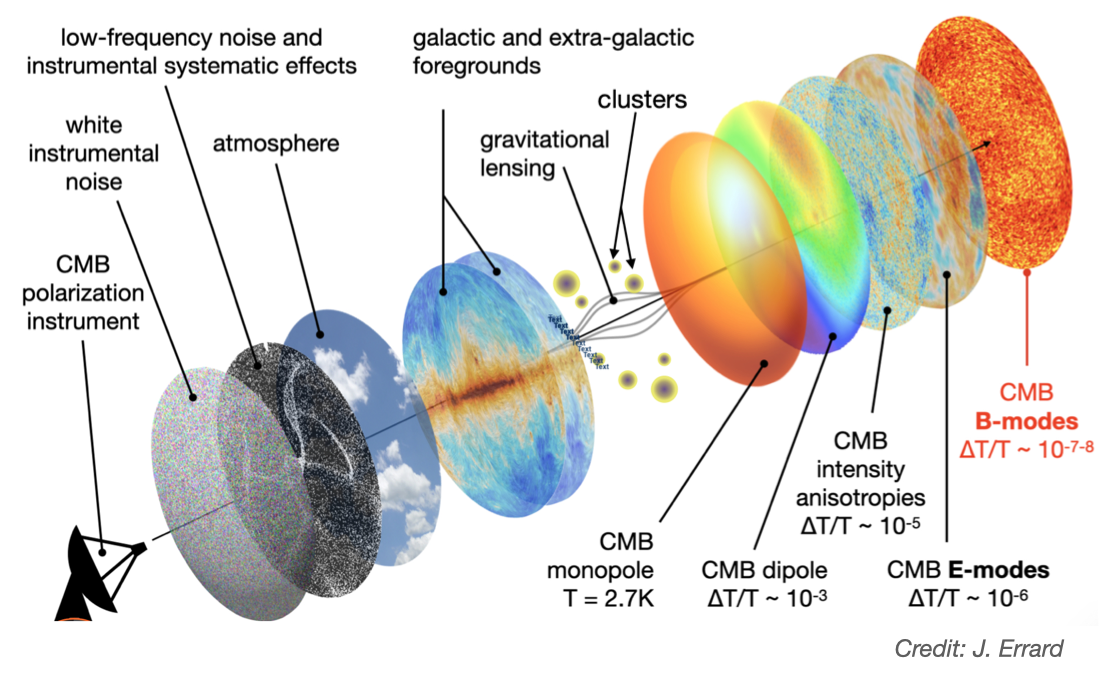

According to the current dominant cosmological model, our Universe was born 13.8 billions years ago as a very hot and dense plasma, rapidly expanding and cooling down: this birth is commonly known as the Big Bang. During the early ages, this plasma was so dense that light was tightly coupled to it and could not escape from it. When cooling, the Universe evolved from this very dense, optically thick state to a less dense and cooler state. The first atoms formed, and photons escaped: the Universe became transparent to light, 380 000 years after the Big Bang. The moment when CMB photons are emitted is commonly refered to as the last scattering surface.

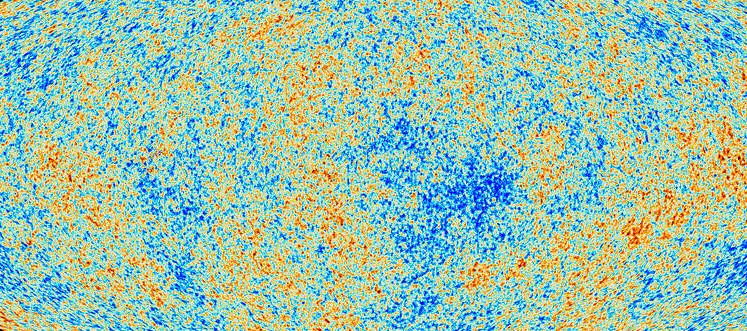

These photons have since then been traveling through space and time, cooling with the ongoing expansion of the Universe. Observed on Earth today, they form a spatially uniform and diffuse signal in the microwave domain: the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). The spectrum of the CMB is an almost perfect blackbody with a temperature of 2.7 K, corresponding to the temperature of the initial plasma redshifted by cosmic expansion. The observation and characterisation of the CMB and its features is one of the major domain of interest in modern cosmology.

Evolution of the Universe since the Big Bang (©: ESA – C. Carreau)

Inflation

In the 60's and 70's, first observations of the CMB and of the Universe at large scale have led to huge breakthroughs in our comprehension of cosmic history, but have also brought new questions. Two main characteristics of our Universe are indeed that it is flat – its global geometry shows no curvature in the context of Einstein’s general relativity – and isotropic – its content is the same, regardless the direction of observation.

However, according to the “classic” Big Bang model, regions of the sky separated by more than a few degrees should never have been in causal contact, so there is no particular reason for these regions to have a similar matter and energy content, or for the CMB to be almost uniform. Moreover, general relativity allows the Universe to have any curvature parameter between -1 (hyperbolic geometry) and 1 (spheric geometry), so why do we measure zero with a high level of confidence, which corresponds to the very particular case of flatness?

To solve these problems, the theory of inflation has been proposed and developed in the late 70's-early 80's. This theory – or more accurately this group of theories – postulates the existence of a extremely short and rapid phase of expansion at the very beginning of the Universe – lasting less than 10-33 seconds after the Big Bang! This expansion would explain how regions of the sky could have been in causal contact even if they are far apart today, and also would have flattened the Universe. It would also explain how initial quantum fluctuations have been magnified to give birth to the actual large scale structures, such as galaxies and cluster of galaxies.